As we become more experienced in the professional practice of our organizational function, we build a repertoire of “recipes for success” — mental models that indicate what methods to use for solving various types of problem, and criteria for evaluating how well we succeeded in achieving specific outcomes.

Assemble a group of people from different functions – for example the typical project group or management taskforce that is used for problem-situations that span organizational boundaries and you discover that its members’ perspectives diverge – and often conflict.

Organizational boundaries separate communities of practice: groups with distinct ways of working, with separate cultures, values, and goals. Various functional or specialist groups (e.g. accounting, marketing, or engineering) have different criteria for success.

These differences produce confusion and conflict when changes need to span group boundaries for business processes to work. E.g., Marketing often attempt to sell products that are not technically feasible, as they have little understanding of engineering constraints.

“Consensus planning” is the worst strategy for resolving wicked problems, because it assumes easily-agreed objectives and a one-size-fits-all solution.

Instead, we need to use problem–exploration techniques that allow stakeholders to engage in collaborative learning about what other groups wish to achieve and what work needs to be done to achieve these diverse objectives.

Appreciative design makes sense of this tangle of complexities, using an interactive approach to incorporate the multiple, mutually inconsistent stakeholder aims into a coherent change plan:

- It explores the “flow” of work-processes in the area of practice in which we perceive problems;

- It inquires into and appreciates the context of work, exploring organizational culture, values, and relationships between those involved in the problem-situation;

- Finally, it produces alternative, context-specific models of work-processes based on competing objectives and cultural values. These act as the basis for discussion across workgroup boundaries.

Before we start defining how things need to change, it is important to explore the work that is done and the diverse objectives it fulfills.

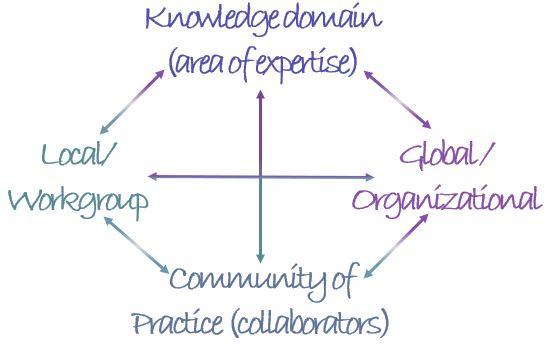

Differences in perspective across group boundaries can be understood by exploring interactions between stakeholder groups:

- The goals, values, and culture of diverse, local communities of practice (e.g. accounting or engineering) vs. those of global (organizational) stakeholders such as senior management;

- The knowledge, practices, and criteria-for-success of various communities of practice vs. the formal standards and expertise assumed in the wider knowledge domain (e.g. accounting).

The idea is to model and explore what work needs to be done, how, and why. Members of various groups can then understand the wider processes and interactions across group boundaries that make the organization work, buying into changes that make them, collectively, more effective.

An effective strategy for boundary-spanning design and change-management explores the problem-situation iteratively, incorporating the implicit knowledge that surfaces during investigation, acknowledging multiple ways of framing the situation, and managing evolving strategies, contingencies, and values to produce a coherent set of priorities for change. It involves three, very different types of thinking:

1

Co-Design of Business & IT Systems

Boundary-spanning design is improvisational. We very rarely understand all the requirements for change, even when we start to implement changes to business processes and IT systems. The key skill is an ability to adapt to contingencies, integrating group knowledge across work domains.

Adaptive planning takes an iterative approach to goal-setting, integrating knowledge about what needs to be done with an evolving appreciation of how the organization works. We center this around an effective business strategy for our company, while prioritizing the work processes that those involved identify.

Read more on the Co-design of Business & IT Systems

2

Systemic Thinking

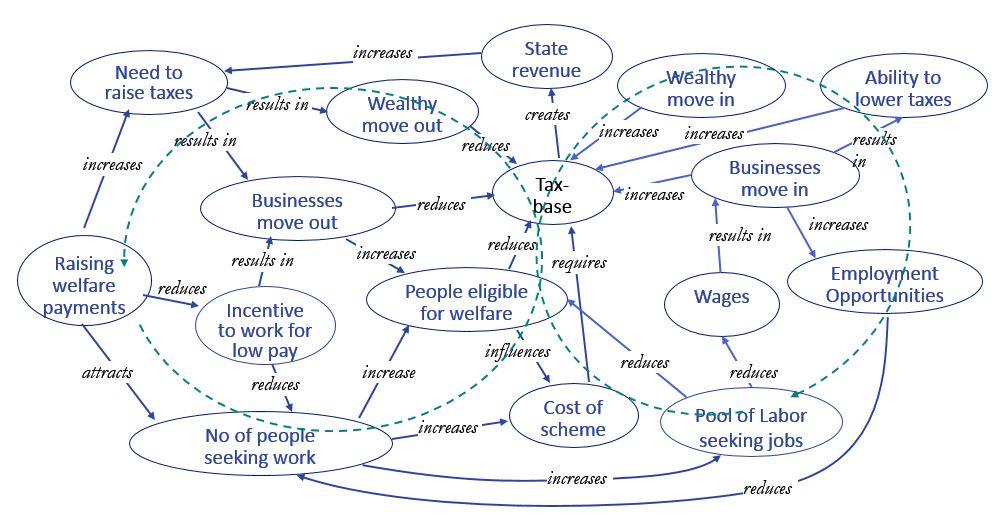

In a complex, interconnected world modern organizations need to focus on effectiveness – doing the right thing – rather than the efficiency focus of most design approaches. We still use late 19th century thinking in design, trying to use “scientific management” rather than centering the process on how people need to do their work in order to produce products and services that are responsive to customer needs.

Systemic thinking takes a “big picture” approach to problem investigation, followed by a “divide-and-conquer” approach to making improvements.

Read more on Thinking Systemically

3

Analyzing Wicked Problems

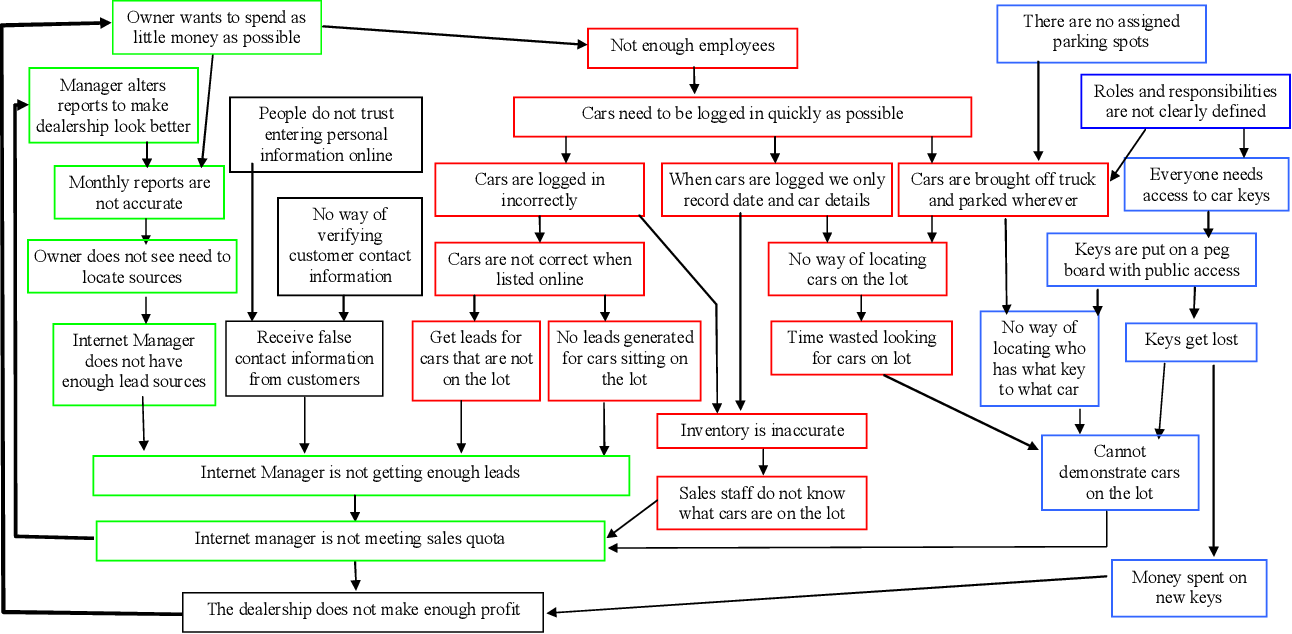

In the design of business process and IT change, we typically define a single goal that conflates the multiple, often conflicting, objectives of the work-systems we are trying to improve. Complex problems, that everyone defines differently, are known as wicked problems.

Focusing on a single goal complicates, rather than simplifies the design of work-systems, as we inevitably have to revisit these goals to accommodate the perspectives that we ignored, reworking the analysis to incorporate the multiple other purposes that people value. Many times, objectives conflict, but we don’t realize this because we only have a vague idea of what these are.

Human-centered design starts with the work that people need to do, involving them in the redesign. Unless we understand what needs to be done, we can’t design systems to support work.

Read more on Wicked Problems