What’s Wicked about organizational change problems?

Wicked problems are so-called because they lack any single cause or structure. They are often described as “messes” or tangles of interrelated problems – each of which is framed by various stakeholders in multiple ways, depending on their experience and location in the organization.

The concept of wicked problems was first explained in a paper about organizational planning whose authors, Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber, argued that organizational planners deal with complex systemic problems, that are impossible to resolve using analytical methods. They labeled these problems “wicked” problems, to distinguish them from the “tame” problems that scientists and systems developers typically deal with, and that can be solved using logical analysis methods. While tame problems can be defined in terms of goals, rules, and relate to a clear scope of action, wicked problems consist of many, interrelated problems, have vague, emergent goals and boundaries, and are negotiated among stakeholders who hold radically different views of the organization (Rittel & Webber, 1973). In the same year, Herbert Simon published The Structure of Ill-Structured Problems, in which he contrasted well-structured, rule-based problems with ill-structured problems, which required investigation, bounding, and analysis before they could be resolved (Simon, 1973). Russell Ackoff (1974) went one step further, describing organizational problem-situations as “messes” that required negotiation to define and could only be assessed subjectively. Wicked problems are therefore characterized by the following attributes:

- The problem definition depends on the solution: any definition of a solution depends on how the problem is framed and vice versa;

- Multiple problems co-exist: various stakeholders have radically different world views and understand the problem differently, depending on where they are located in the organization (what parts of the problem they experience in their functional group);

- Problems are interrelated: because stakeholders only ever see part of the problem, it is impossoble to define the whole scope of the problem. Solving one person’s problem may make other peoples’ problems worse;

- There are no criteria by which to evaluate a solution: because the problem cannot be defined objectively, it is not possible to define criteria by which we will know if we solved the problem;

- Problems evolve: not only does taking action change the situation, but also the business environment is constantly evolving in unpredictable ways;

- The problem is never solved definitively: every time a change analyst takes action (implements a solution), this changes the problem-situation. The constraints that the overall problem is subject to, and the resources needed to solve it change over time.

Because they are so complex, wicked problems cannot be resolved using structured (logical) analysis methods. We need systemic analysis approaches that use a divide-and-conquer approach to surface multiple problem perspectives. This allows stakeholders to represent their ideal work-system(s) and to debate what needs to change.

Analyzing Wicked Problems

We normally start any problem investigation with a stakeholder analysis, where we define the problems experienced by various organizational stakeholders (normally group managers or boundary-spanners) then attempt to integrate them. Every stakeholder will have a different (and partial) understanding of problems.

To negotiate a solution, you must:

(i) Determine a suitable system boundary

– For the “information system” of human-activity

– For the computerized information system (IS)

(ii) Determine the goals of design (from various perspectives)

(iii) Facilitate stakeholders, in merging these multiple goals into a set of prioritized outcomes.

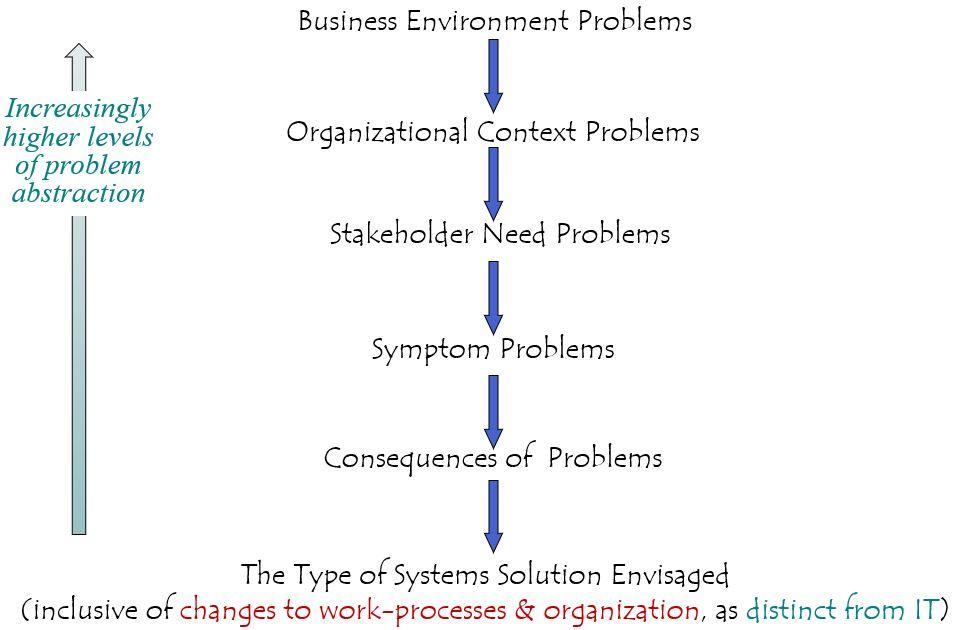

The systemic problem-analysis approach presented here provides a way of managing this analysis. To understand the problem, we need to appreciate that any business problem can be modeled at different levels of analysis, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Various Levels of Analysis, When Investigating Problem Cause-and-Effect

There are two big issues that complicate problem analysis:

1. Most stakeholders will tell you about symptoms – various parts of the bigger problem that they experience – rather than the root-cause problems,that need to be resolved. Integrating these results in a lot of “partial perspectives,” or problem-fragments that it is your job to assemble;

2. Stakeholders are not usually aware that what they describe as “the problem” is actually a set of interrelated problems. These need detangling and separating out.

Typically, IT systems analysts are taught to define requirements for a solution. They are really bad at defining the problem they are trying to solve! For example, if we employ a problem-statement typically used in requirements analysis, we will get something like:

Initial Problem Statement

| Element | Description |

| The problem of … | Order processing is too slow and prone to human error because this is done manually. |

| Affects … | Customers, order processing staff, order fulfillment staff, complaints staff and managers. |

| The impact of which is … | Orders are not processed in a timely manner, some orders are never dispatched, and some customers receive the wrong items. |

| A successful solution would be … | A system to automate order-processing would eliminate errors, provide more time for order processing staff and order fulfillment staff to get on with their work, and increase customer satisfaction, resulting in more business. |

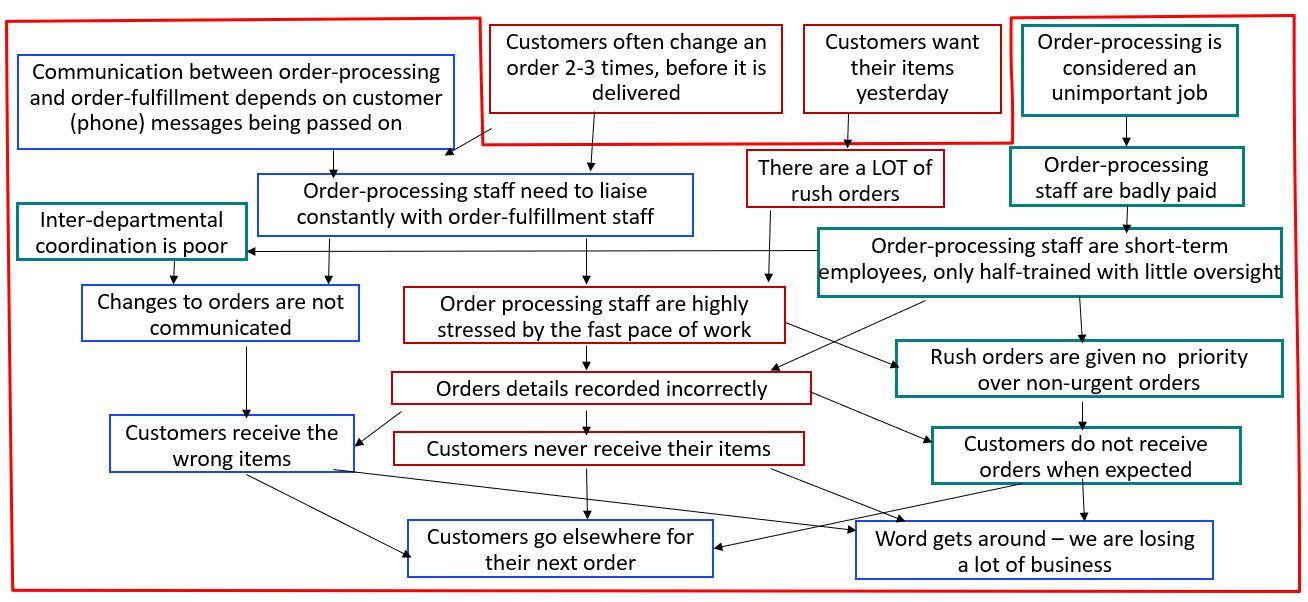

This problem-statement focuses on how the IT system will function (a typical mistake). If the analyst is questioned, they will state that the problem exists because a process is performed manually, rather than being automated. But when asked what work needs to be automated and why, they are unable to define this. A better definition of the problem focuses on what is not being done effectively. To understand what these problems are, and what causes them, we need to perform a cause-and-effect analysis of order-processing work problems before defining the problems in sufficient detail to solve them. This is shown in Figure 2. It is produced in collaboration with the people who do the work (and their managers). For each problem identified, participants in order-processing are asked “why does that happen?” Issues at each problem-level have multiple causes and multiple consequences.

Figure 2. A Cause-and-Effect Analysis of Order-Processing Problems

As you model problem cause-and-effect relationships, it becomes apparent that some problems are outside the scope of what we can influence. This is indicated by drawing a (red) boundary-line around the problems that we can affect. It also becomes apparent that the problem-elements can be separated into three distinct clusters that are concerned with different causes of the problem. These are outlined in different colors in Figure 3. That analysis allows us to define the “what is not being done effectively?” aspect of the problem in more detail.

Improved Problem Statement: What is not being done effectively?

| Element | Description |

| The problem of … | Order processing is too slow and prone to human error because staff who don’t know what they are doing have no way of recording what has been done to process an order, and no way of tracking the status of an order. |

| Affects … | Customers, order processing staff, order fulfillment staff, complaints staff and managers. |

| The impact of which is … | Orders are not processed in a timely manner, some orders are never dispatched, and some customers receive the wrong items. |

| A successful solution would be … | A system to record and track order-processing activities would eliminate errors, provide more time for order processing staff and order fulfillment staff to get on with their work, and increase customer satisfaction, resulting in more business. |

This definition defines the reason(s) for the problem, in terms of how the system of work is going wrong and why. But conflating the three different aspects of the problem into a single problem-statement makes it difficult to define exactly how to solve it. We get bits of each part of the solution, with no clear way to evaluate if we have solved them all. The giveaway is that the problem-definition has three separate elements that are combined in one single problem-statement. If we separate these out, we get three targeted problem definitions:

Problem Statement 1. Focus on Staff Training and Management

| Element | Description |

| #1: The problem of … | Order processing staff make mistakes and do not process orders according to delivery date order and priority because staff are not trained in effective work procedures and lack any formal oversight mechanisms to ensure that they process orders according to priority and expected delivery date |

| Affects … | Customers, order processing staff, order fulfillment staff, complaints staff and managers. |

| The impact of which is … | Customer dissatisfaction – customers do not receive correct orders, or do not receive orders for which they have paid, because staff do not check order items are correct and complete before dispatch, staff do not process orders to meet delivery dates, and staff are unaware of order priorities. |

| A successful solution would be … | A system to define and manage the rules and priorities for effective order-processing would ensure that staff process orders according to delivery date and priority, increasing customer satisfaction and resulting in more repeat business. |

Problem Statement 2. Focus on Order Recording, Status, and Progress Tracking

| Element | Description |

| #2: The problem of … | Order processing is too slow and processed out of order because there is no way of recording what has been done to process an order, and no way of tracking the status of an order. |

| Affects … | Customers, order processing staff, order fulfillment staff, complaints staff and managers. |

| The impact of which is … | Customer dissatisfaction – orders are not processed in a timely manner, rush orders are not prioritized, some orders are never dispatched, and some customers receive the wrong items. |

| A successful solution would be … | A system to record and track customer order progress would flag orders that have not been processes, communicate order status, and monitor progress, allowing problems to be detected before they affect customers. |

Problem Statement 3. Focus on Coordination of Order Status and Processing Across Departments and Between Individual Staff

| Element | Description |

| #3: The problem of … | Order processing is prone to human error because order processing stages are poorly coordinated between individual staff and across department boundaries. |

| Affects … | Customers, order processing staff, order fulfillment staff, complaints staff and managers. |

| The impact of which is … | Customer dissatisfaction – orders are not processed in a timely manner, rush orders are not prioritized, some orders are never dispatched, and some customers receive the wrong items. |

| A successful solution would be … | A system to communicate the progress of each order would ensure that each order is processed in a timely manner, prioritize rush orders, and coordinate order-processing activities across departments. |

To summarize, each stakeholder will have a different understanding of:

– The core problems and their causes

– The scope of the organization affected (required solution boundary)

– Priorities for change.

By exploring the causes of the “symptom” problems reported by stakeholders, then merging them into a cause-and-effect diagram (with input and validation from stakeholders), we can analyze related clusters of sub-problems, to understand the problem that we are solving in detail. This allows us to separate out different aspects of the problem, to ensure that we define a solution that covers all the issues that we need to change.

Systemic Problem Solving

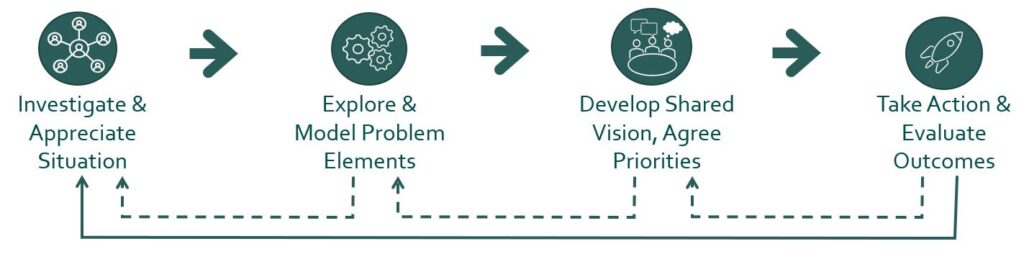

Wicked problems need a systemic approach to problem-solving that investigates and models problems from a human-activity perspective before attempting to define solutions. In IT design, we tend to define requirements for a solution with very little inquiry into the problem. Systemic approaches spend more time on inquiry – the solution just follows from the definition of the current problem. I emphasize “current problem” because a systemic approach recognizes that wicked problems are too complex to define or resolve all at once. We therefore need a divide-and-conquer approach to problem-solving, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. A Systemic Problem-Solving Approach

Any effective approach to solving wicked problems must be iterative. It must identify subsets of the problem, investigate these, model how various elements of the problem are related, and then develop a shared vision across stakeholders for how to resolve this subset of problems, before taking action to implement the negotiated solution. At each stage, you may need to revisit aspects of the problem determined at a previous stage:

- As you explore and model problem elements, you may need to perform more investigation in order to understand these elements better;

- As you develop a shared vision for the solution and agree how to resolve these aspects of the problem, you may need to explore problem elements in more detail and revise the models of how they are related, both to other problem-elements and to the business environment and goals;

- As you take action to resolve the problematic situation, you may need to revise your scope or focus, as the feasibility or implications of change become clear. At this point, you may need to revisit the shared vision and priorities with stakeholders, to resolve these constraints;

- Following implementation of the agreed solution, you will need to investigate and appreciate the situation now. Making changes means that the “big picture” problem will have changed.

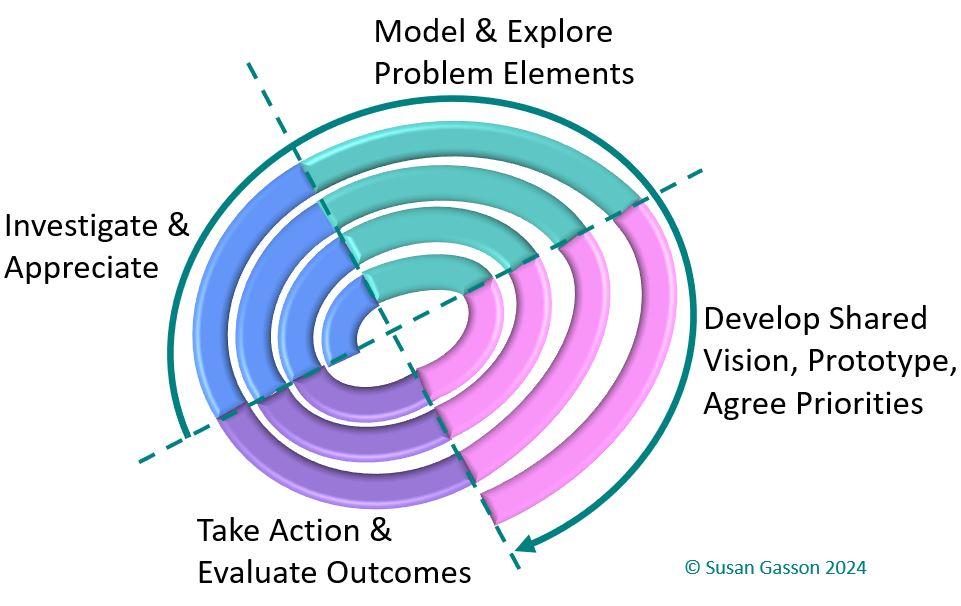

Any systemic changes have waves of consequences, only some of which can be anticipated and modeled in advance. Other consequences only become apparent after a time-lag, at which point remedial action may be required. We therefore need an iterative planning approach – one that models how the organization works now, at the start of each cycle of change. This is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. An Iterative Approach to Systemic Change Management

The spiral follows the stages of analysis shown in Figure 3. Each cycle breaks off a different subset of problems, which are modeled, defined, and refined in the second stage. Of course, there is feedback between stages – as shown in Figure 3 – because you need to explore stakeholder perspectives in more detail as you produce problem cause-and-effect models, or rework the clustering of problems into different “sub-systems” of work activity, as stakeholders explore the implications of clustering problems in this way. The third stage produces a set of IT and work-design prototypes that allow stakeholders to explore the implications of defining problems in this way. Once they are agreed that this is how they wish to change things, the fourth stage implements changes across the organization and evaluates the outcomes. We then come full-circle, to investigate what problems we face now …